Making sense of the real world and creating a fictional world

I like the expression “lost possibilities.” To be born means being compelled to choose an era, a place, and a life. To exist here, now means to lose the possibility of being countless other potential selves. (Miyazaki 1996, p. 306)

From a cognitive point of view, the way we create meaning and a world of significance since we are born and during the first three years of life emerges from the response to stimulus through our senses on experiencing the outside world. From those experiences we collect sensations with value, meaning and significance, which we store in our brain as memories. As we start to give order and structure to those memories, we start to create a world of our own, for good or bad, sweet or sour, beautiful or ugly, lovable or indifferent. Later on, children also start to play “pretend” games, in which self-discovery happens, but also the game of creativity and imagination starts on finding new possibilities; for example, by creating an elephant out of a pillow. Very quickly, daydreams, imagination and curiosity start to be useful tools to create a world of our own. Akin to a child discovering and creating a world of their own, the director of animation similarly creates a world of his own, full of fragmented impressions from the real, from his time and place, and also from his inner world of emotions, visions, imagination, dreams allowing a new world to emerge, one that reflects both the real and both an escape from it in worlds of fantasy. As Hayao Miyazaki puts it,

human history exists in a continuum encompassing both the past and the future, but the moment someone is born into this present instant, into 1978, he or she has already lost certain opportunities or possibilities, including the chance to be born in other ages. Yet we can still enjoy ourselves in different fantasy worlds. And this yearning for other, lost possibilities may also be a major motivator for those of us in the industry. (Miyazaki 1996, p.18)

From a historical point of view (Bendazzi 2016), Miyazaki’s work emerges in the late 1960s, from the TV animation industry as an artist, layout and animator. His work as a director emerges in the 1980s. By this time, Japan had suffered by then, a period of strong pessimism, probably due to its geography and historic challenges, such as their WWII defeat, the negative reflection of two nuclear bombs and the reform process from the United States (1970s). While Japanese dystopian works such as Akira (1988) and Ghost in the Shell (1995) appeared (Napier 2005, p. 28, 39), a huge variety of genres and post-modern themes in Japan also emerged. Miyazaki’s response, approach and philosophy projected a very different and more positively-inspired answer to the worries of the world. Approaching global concerns such as environmental protections, war and weapons of mass destruction, and how children would grow up in the context of these issues, he espoused a more ethical and positive answer to how best to deal with these challenges, inspiring journeys of survival and change. Miyazaki created worlds which are remarkably human and emotional. At the core of his approach we observe an intention, not only to depict these worries about reality and neither an interpretation of it, but a clear intention to transform the conflicts of the world into places of liberation, reform and positive faith.

Miyazaki’s views on animated film: Liberation from the real

The work of a director is a result of an individual viewpoint, linked to a certain era and place, perceived and filtered by conscience and values about the world he lives. From his frame of reference, culture and imagination, the director, makes choices and gives visibility to universes of meaning and significance of what he wants to express, propose or transform. In Miyazaki’s case, the context and frame of reference of his work projects the possibility to tell a story, which is rich in impressions about the real but also impressive, extravagant and imaginative in imagery of fantasy. As Miyazaki explains, an animated film gives visibility to a universe that already exists inside the director’s mind and heart. He contends, “inspired by that trigger, what rushes forth from inside you is the world you have already drawn inside yourself, the many landscapes you have stored up, the thoughts and feelings that seek expression” (Miyazaki 2009, p. 27, 28).

From deep impressions of reality, thoughts dreams, and emotions, Miyazaki’s universes reflect profound views about life, but which also offer the opportunity for the audience to feel liberated, to be free, and to be open to achieving new goals. According to Miyazaki, animation should, “offer a sense of liberation to present-day young people who, in this suffocating, overprotective, and managed society, find their path to self-reliant independence blocked and have become neurotic” (Miyazaki, 1996 p. 251). Being liberated from the real allows the viewer to feel joy, to relax and to feel free from the weight of the real in universes the audience can also escape. As Miyazaki explains further, “I think cartoon movies above all help our spirits relax, they make us feel happy, and they make us feel refreshed. And while doing so, they mays also allow to escape from ourselves” (Miyazaki 1996, p. 306). As such, animated films allow this escape from everyday pressures by constructing fantastic universes, which enables viewers to embrace strength, bravery and being more heroic about their struggles:

We lived trapped in ourselves, imprisoned in the real world. But if we can free ourselves from the various complexes we have and the tangled relationships we are in to live in a freer, more open world, we might be able to become strong and heroic. I think everyone entertains thoughts of becoming more beautiful, or more gentle, or of having a more meaningful existence. (Miyazaki 1996, p. 306)

Miyazaki’s film worlds offer the opportunity to countless possibilities, as places where we can project our hopes and dreams with no constrains of the real, and which in animation can take any meaning, form, or movement. In this sense, the possibility of a new existence opens up for the audience, and by extension, society as a whole. Miyazaki asserts that the purpose of “the fantasy worlds of cartoon movies so strongly represent[s] our hopes and yearnings” (Miyazaki, 1996, p. 307). Predicated on the worries and vulnerabilities of adult life and the possibility of escape, freedom and liberation in universes of fantasy, Miyazaki’s films blend together both worlds, which then becomes deeply human and emotional and both magical and liberating investing in a construction of meaning that allows transformation, change and a positive answer for both characters in the film and for the viewers.

Creating “fictional and fantastic” universes

Miyazaki is on record (1996, 2009) as characterizing the animated film as a place of fantasy, escape and liberation, and transformation. Because his films appeal to hopes and inner emotions, they evoke the possibility of hope and new modes of existence and wherein viewers can find common ground, despite being a form of “escapism” (Miyazaki 1996, p. 307). He continues,

Cartoons are a fake world. Because cartoons are fake, they disarm viewers, making them think they are ‘just cartoons.’ Liberated from reality and relaxed, viewers find themselves pulled into scenes showing the protagonists and a cartoon world and then may find that that experience evokes secrete hopes and longings in themselves. (1996, p. 307)

Inherent to Miyazaki’s discourse is the intention of confronting the audience with issues, deep truths and impressions about reality which – by taking place in universes of fantasy – defy our reality in form, behaviors and systems of physics. In animated films, styles, forms of representation, techniques, behaviours can be very diverse, but at its essence, animation alters and transforms the nature, logic and physics of the real into universes of countless possibilities in: time, place, order, physics, powers, behaviour and meaning. In the process of constructing these “escape” worlds, Miyazaki acknowledges the importance of aesthetic coherence when fabricating a fictional world, but which must be as credible as possible so the viewers can engage with it and as well find some meaning and truth. He asserts, “anime may depict fictional worlds, but I nonetheless believe that at its core it must have a certain realism. Even if the world depicted is a lie, the trick is to make it seem real as possible. Stated another way, the animator must fabricate a lie that that seems so real viewers will think the world depicted might possible exist” (Miyazaki 1996, p. 21). In this fashion, fictional and fantasy worlds become the stage to recreate new possibilities of meaning and existence to the viewers due to credible constructions of form and movement. The ways by which these fantasy worlds are constructed offer a new order of a universe where substitutions from the real happen in the ‘always possible worlds’ of animation, and conveying new meanings. In Theory of Semiotics, Umberto Eco argues that “Every time there is possibility of lying, there is a sign-function: which is to signify (and then to communicate) something to which no real state of things corresponds. A theory of codes must study everything that can be used in order to lie” (1979, p. 58). According to Eco, graphical signs offer the possibility to inform and to signify something completely fabricated. Similarly, Paul Wells contends that a “symbol invests its object with meaning […] and it is defined by a series of substitutions. In the narrative progression animation liberates the symbol and its attendant meaning from material and historical constrain, enabling evocation, allusion, suggestion and above all transposition” (1998, p. 83-84). In animation, signs, symbols and graphical language (conceptual graphical structures) and movement (continuous graphical structures of behaviors) create the new possibility of existence and meaning to which no real state of things corresponds. The universes of Miyazaki’s films are fictional places which communicate, inform and give visibility to worlds that transform the everyday into something new, with new meaning and significance to provide the audience with examples of escape, change and a better world for all.

Analysis of case study: Category of universe

Miyazaki’s film universes arise from a pattern of inspiration that combine two different aspects: inspiration from historical events, as well as being inspired by fiction, fantasy and imagination. Historical events constitute a rich, huge and multicultural frame of reference, which reflects the director’s deep global concerns and provides his particular sensibility and visual style (Miyazaki 1996, 2014). This reflects dramatic actual events (wars, diseases, earthquakes, or weapons of mass destruction), vulnerable groups of people (mine workers, lepers, and tuberculosis sufferers), and above all a sense of humanity, arising from the characters’ truthful journeys. Viewers also relate to the characters’ emotional experiences which often echo their own (children growing up, making a living, overcoming feelings of insecurity, the need for love, peaceful existence, friendship and affection). Films inspired by fictional works are usually based on novels, legends, poems and children’s books across cultural boundaries (Eastern and Western) and across history, with an abundance of extravagant and imaginative imagery. The result is universes which combine legible aspects of our ordinary world which are human, emotional, and very familiar to the viewers, yet blended into worlds which elevate viewers into places of fantasy. This blend makes Miyazaki’s films unique, full of liberation, magic, delight, and dream, but which always carry some truth in it. Miyazaki himself acknowledges that the audience knows “that what they are seeing is fake, that it can’t be reality, but at the same time they sense deep in their hearts that there is some sort of truth in the work” (Miyazaki 1996, p. 308).

Universes: Origins, Inspirations from fiction and from reality

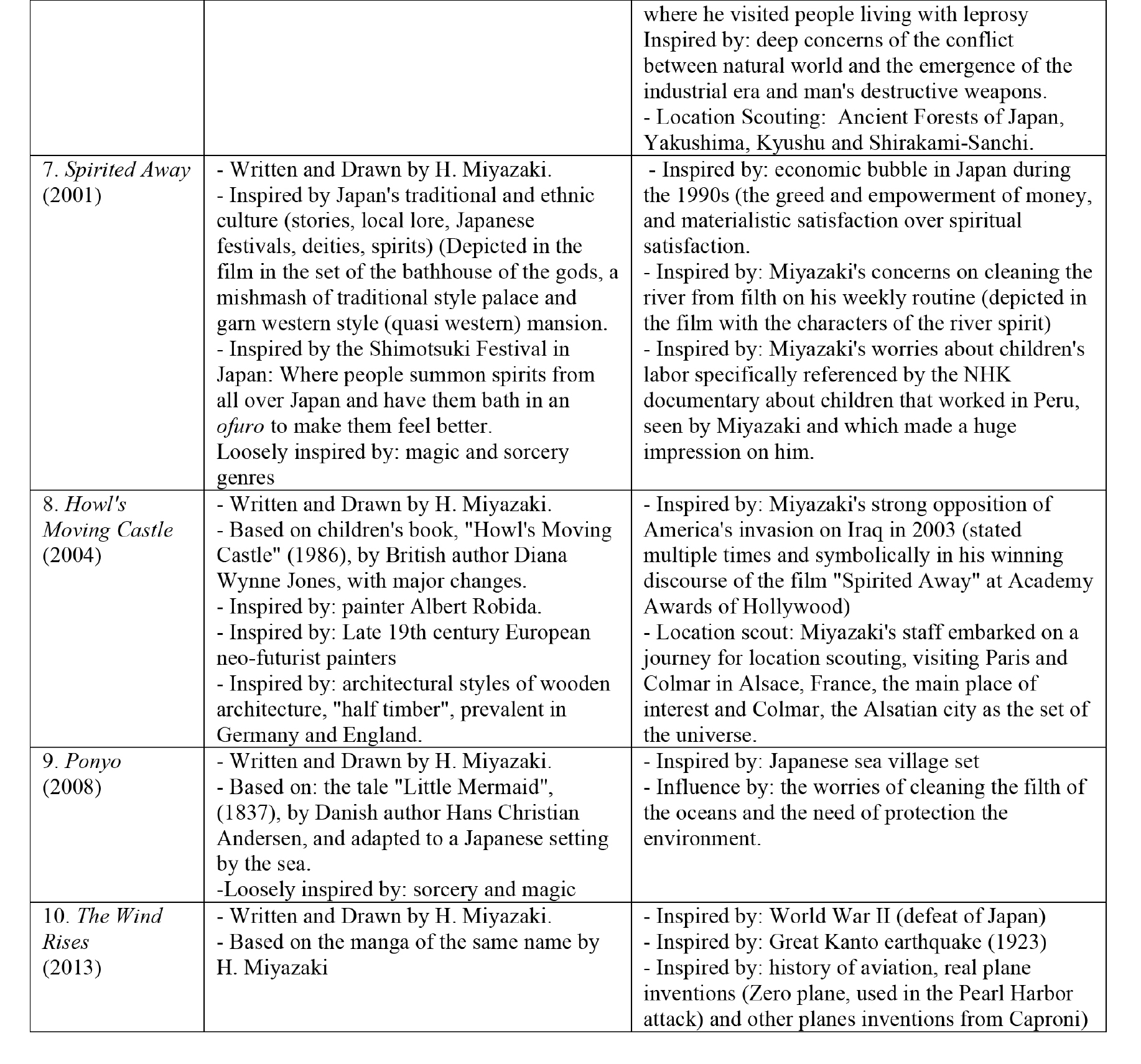

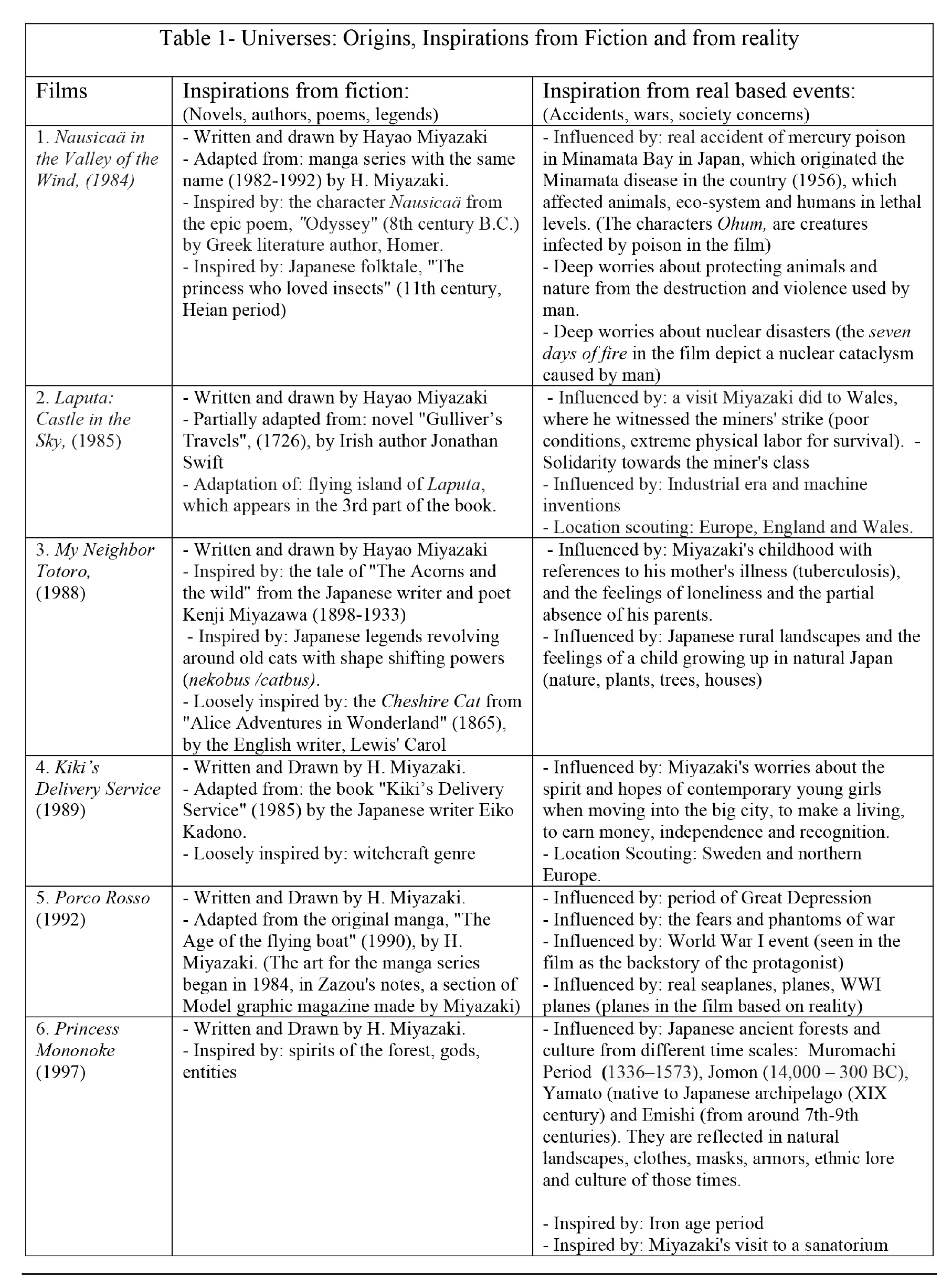

In Table 1 below, we outline the observed occurrences of Miyazaki’s universes regarding: origins of the stories and inspirations from fiction and real based events.

As Table 1 above reveals, Miyazaki is the author of three of the original stories adapted from his own manga for the screen: Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Porco Rosso and The Wind Rises. In this case Miyazaki is the author of a considerable body of artwork, concepts and storylines, which came directly from his own material. The other seven films were inspired by or were adaptations from literary works (for example, the character Nausicaä is inspired by Homer’s The Odyssey). Gulliver’s Travels (Swift, has elements that occur also in Laputa: Castle in the Sky; the tale “The Acorns and the Wild” by Japanese poet Kenji Miyazawa (1898-1933) inspired parts of My Neighbor Totoro), and Ponyo contains elements from “The Little Mermaid” (Hans Christian Andersen. Kiki’s Delivery Service was adapted from the novel by the Japanese writer Eiko Kadono; similarly, Howl’s Moving Castle was adapted from the original novel by Diana Wynne Jones. For both original stories and adaptations, Miyazaki’s films come to life on screen through the gesture of his hand, in a long and detailed process of drawing the ekonte (continuous sketches, which are more detailed than common storyboards), image boards and conceptual art generated in the first stages of creation, rather than starting the process by first adapting a script. Although after this period of pre-production, the rest of the studio team gets involved, the director is responsible for the creation of all storylines and imagery.

The second type of inspiration, which was more surprising to us, were those which emerged from actual historical events, reflecting a human perception and sensibility of the reality of our lives at the level of significance, which – when depicted on the screen – creates empathy congruent with our lived experiences. In the ten films, these events appear as a point of departure of the story depicting humanity in various harsh contexts, which throughout the films evolve into a fantasy world which tends to be more easily resolved and transformed into a better end for its characters. Miyazaki draws from historical events such as the 1956 Minamata mercury poisonings (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind), World Wars I and II (Porco Rosso, The Wind Rises), historical leper colonies (in Princess Mononoke), the miner’s strike and poor conditions of survival (Laputa: Castle in the Sky), the economic bubble period (in Spirited Away), environmental concerns and the need for legislative protection (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, My Neighbor Totoro, Princess Mononoke, Ponyo, Spirited Away, and worries about nuclear disasters (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind). Miyazaki’s own life experiences – his mother’s recovery from tuberculosis (My Neighbor Totoro) and his opposition to America’s invasion of Iraq in 2003 (Howl’s Moving Castle) – also combine to create a recurrent pattern concerned with children growing up and facing the challenges of their own survival and the future of their universes. These events provide a truthful sensibility and perception about our world, which – when embraced and overcome by the fictional characters – are exposed to changes offering a liberation from an intolerable filmic existence. The mesh of inspirations for Miyazaki’s universes reveal aspects that – although harsh when filtered by the director’s ethical and positive view and exposed to fantasy aspects – offer liberation; evoking messages of change, reform, and positive possibility to its characters which makes them profoundly appealing to viewers. As such, Miyazaki’s universes act as a transforming machine for real events via fantasy storylines.

Universes: Time, Place and Physics

Embedded in the storylines, a physical and graphical universe emerges, which exhibits the same fracture between the vulnerabilities of the real and the possibility of escape through fantasy (which depicts in form and movement universes that can almost be real but at any second shift into places that we could not experience in reality). Miyazaki creates worlds wherein references of cityscapes, natural landscapes, references to global events, and targeted groups of people co-exist with a level of eccentricity characteristic of fantasy, such as flying islands and walking castles – a peculiarity of design of its inhabitants (non-human characters, half-animal, half-human characters, monsters, beasts, gods, curses, entities) with a unique blended vision of these two extremes. The result is universes with their own fictional times, places, systems of physics and logics which are possible in animation and which reflect the combination of our lived world with the mental and inner activity of imagination in one single universe – the universe of the director.

When in motion, Miyazaki’s universes depict many kinds of systems of physics and logics of behaviours, such as magnetic energies, supernatural powers, sorcery, magic, spiritual entities, floating, flying, other anti-gravitational abilities, magnetism and extravagant metamorphoses of physiologies and behaviours. But it is the confrontation between real and fantasy which makes them so powerful and rich, offering an experience in time to which viewers can relate, engage, experience and believe, although these universes don’t exist in our reality. The credibility of such a mesh of events in motion in Miyazaki allows a positive transformation, reform and better end to the universe of its inhabitants. When graphically consistent and coherent in movement and behaviours, these universes present a new and credible experience to the audience. Accordingly, Miyazaki argues that animated films

are not meant to expound on complexes, themes or theories, and I don’t think there’s any need to insist on them being art either. They start to be preposterous, so its all right to depict absurd settings or tell bald lies – viewers accept this. But the creators need to try hard to make their fake worlds seem as real as possible. It’s not good enough to just string together a bunch of clever ideas, for the effort required is fundamentally different. Lies must layered upon lies to create a thoroughly believable fake world. Its an imaginary world, but it should seem to actually exist as an alternate world, and the people who live there should appear to think and act in a realistic way. […] I think the trick here is tuning the lies you create into a single, coherent world. (Miyazaki, 1996, p. 307)

As Miyazaki explains, although imaginary, universes must provide some truth, and be treated coherently as if they could exist. In his body of work, these universes allows a dichotomy of values where a war can exist but peace can be achieved (Nausicaä in the Valley of the Wind), humans can turn into pigs but they can revert to human shape due to sacrifice and compromise (Spirited Away), a girl can make a living and be independent if she overcomes her fears (Kiki’s Delivery Service), animals and nature might co-exist humans there is a compromise towards a peaceful resolution (Princess Mononoke). This fracture between the vulnerabilities of the real and the hopeful possibilities of fantasy produces at the level of meaning, an investment in the transformation of its universes into places of reform, ethical, peaceful and tolerable existence for all.

One of the recurrent patterns of Miyazaki’s filmic universes is the constant liberation from the ground into the heights of the skies. Flying, floating, or other forms of levitation are present in almost all the films of our case study (with one exception). Either by the power of wind-powered glides (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind), crystal magnetism which allows natural floating (Laputa: Castle in the Sky), spiritual entities such as gods and spirits which can grow into the heights (Princess Mononoke), magical sorcery that allows Kiki to fly (Kiki’s Delivery Service), or which allows Howl and Sophie to perform a sky walk in the sky (Howl’s Moving Castle), vehicles such as planes or seaplanes (Porco Rosso, Laputa: Castle in the Sky, The Wind Rises), or characters flying in the skies (My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle) in almost every film we encountered a scene in which characters defy the rules of gravity and take to the liberation of the skies, by flying, floating, falling or are taken above the sky by themselves, others or by vehicles. Physics plays a major role at this level of fantasy as the scenes unfold, portraying a series of different logics allowing liberation from the constraints of the real world. As Cavallaro acknowledges (for example), “above all, Laputa incarnates the pivotal lesson regarding the manipulation of time in animation as the key factor behind the essential quality of animation as an art form and medium – namely, its disengagement from the laws of physics – and to some extent of logic too” (2006, p. 67).

According to Napier, this defiance of gravity evokes freedom, change and redemption. As she notes further, “in these soaring images, from gliders and warplanes to the flying island of Laputa to Nausicaä’s climactic walk through the sky, Miyazaki’s vision reaches its most magical heights, suggesting the possibility of freedom, change and redemption” (2005, p.154). Similarly, Lamarre (2009) argues that Miyazaki’s depictions of flight provide funny and whimsically vehicles and an avoidance of ballistic or military approaches to flying machines. “All in all, such funny and eccentric vehicles, often with lots of flapping legs or spinning arms that make them whimsically accessible to the human body, seem calculated to avoid streamlined ballistic-designed craft. Miyazaki studiously avoids jets and rockets, and when he cites such designs, they are closely associated with the evils of war (in Howl’s Moving Castle in particular)” (Lamarre 2009, p.61).

The relation of physics and logic with the construction of meaning in animation is essential, as it puts the world in motion and in another state of things and giving visibility and existence to a universe. Time, place, logic and physics act as new possibilities which can be achieved by the essence of frame-by frame and continuous eternal transformation in animation. In Table 2, we outline the graphical construction of Miyazaki’s universes in time, places and systems of physics or logic, which defy our reality either via changes of state (protagonists’ changes of the state of their bodies), changes of positions (flying, walking in surface of the water, skywalk, float, falling, flying, etc.) or metamorphoses of physiologies or characters (curses, sorcery, shift shape abilities, transfigurations, transformations of physiologies, metamorphoses of bodies, etc.).

As seen in Table 2, universes set in the past, from medieval times (Princess Mononoke) to modern times (Spirited Away) pass through different periods such as the Iron Age (Princess Mononoke), the Industrial revolution (Laputa: Castle in the Sky), to WWI (Porco Rosso) and WWII (The Wind Rises). The films’ locations encapsulate natural landscapes or cityscapes combined with elements of fantasy which – when in motion, define the films’ systems of physics and logic – and by extension, defy our logic of the real. The fantastical aspects of these behaviours are mostly represented in changes of position (flying scenes), changes of state (alteration of the state of protagonist) and transformations of physiologies or metamorphoses (characters, objects, entities). Some examples of these fantastic behaviours include: a walking castle (Howl’s Moving Castle), a bathhouse for the gods (Spirited Away), a flying Island (Laputa: Castle in the Sky), a toxic forest with mutant insects (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind), a girl who runs in a wave made of fish, with a life of its own (Ponyo), a girl who flies a broom in the city (Kiki’s Delivery Service), a pilot with a pig Face (Porco Rosso), and other scenes in which humans characters fly with no other resources than themselves, their ability to enact transformations, or characters with shape-shifting abilities, among others. Fantasy and reality are blended in these universes with their own internal rules, as envisioned by the director’s imagination. Miyazaki describes his process,

usually the lid of my brain lifts after I get in the groove of making the film. Then I think, ah, it’s opened up! But when I’m making a film, I spend all my time thinking not about superficial matters but about what’s going on deep down. I open the door to my subconscious mind. And when that happens, suddenly the threads all connect, and I think, ah, so this is what I really wanted to do all along, but in the real world it may not actually work. And of course if I dive too deeply, I might never come back at all. (2014, p. 227)

In this respect, he blends aspects of our lived world with graphically-constructed fanstasy aspects, which appeal to our experience of the real but which also allow us to experience an escape into worlds of fantasy and imagination, thus making the films appealing for children and adults.

Conclusions: Analysis of level of meaning and category of universes

The analysis of our case study (see Appendix I), in light of the above analysis of the multitude of universes reveals three relevant sub-variables: the original ideas of the stories, inspirations from fiction, and inspirations from historical events, which are depicted in universes with their own times, places and systems of physics. The results of this analysis revealed a mesh of inspirations which combine real and fantasy, from which to unique universes are created, which are arise from the vulnerabilities of the real world and which offer the possibility of change, dream, and liberation in worlds mixed with fantasy. While the origins and inspirations for the stories reveal the frame of reference and intentions of the director, the visual depictions of those universes, through time, place and physics, reveals a system of interactions with motion, which depend on a logic of powers, energies and coherence in order to liberate the universes from the real. Three recurrent patterns of Miyazaki’s universes were found:

(a) Universes which reveal inspirations from historical actual events or worries from the real combined with inspirations from fantasy, allowing a possibility to the viewer to be liberated from the weight of reality and find positive answers.

(b) Universes which are graphically constructed with its own logic of behaviours such as changes of position which offer a liberation from the ground in places or behaviours in the heights of the skies, where characters, objects or sets can fly, float, fall in the skies, defying the laws of gravity and the structures and weight of the real.

(c) Universes which are graphically constructed with its own logic of behaviours, where recurrent transformation and metamorphoses of physiologies of its inhabitants, either by empowering them with energies, sorcery, magic, curses, shift shape configurations, and a confrontation between humans and strange creatures enables liberation to the viewer from his relation with reality.

Miyazaki’s universes are places that cannot possibly exist, yet still provides an escape for the audience – a place to dream and find their hopes and better possibilities for our own world through the ways in which we see and defy the paths of contemporary society. We believe the proposal of Miyazaki invests not only in observation or criticism of the worries of the world, but mostly on the transformation of places of ethical intolerable existence into places of liberation and possible positive existence. These filmic universes reflect and expose Miyazaki’s chronic, intimate and persistent frame of reference fractured between the troubles of the real and the possibility of resolution and escaping in liberated places of dream and fantasy.

Appendix I- Case Study

- The case study of our investigation is focused on the ten feature films listed below.

- The case study excludes Hayao Miyazaki previous work on TV series, at TOEI, A PRO studios and Nippon Animation, where he worked between 1968 and 1979 and also excludes his first feature film as a director named The Castle of Cagliostro (1979), from Tokyo Movie Shinsha, Toho.

- Our case study is focused on his major role as an established director at Studio Ghibli, being “Nausicaä in the Valley of the Wind” considered by Hayao Miyzaki a pre-Ghibli film and the film, which gave path for the studio to emerge and succeed and for that reason also considered in our case study.

- Industry of TV Series:

| Date | TV Series | Design/Animation | Director | Studio |

| 1968 | Little Norse Prince | Hayao Miyazaki | Isao Takahata | TOEI Studios |

| 1971 | Pippi Long stocking | Hayao Miyazaki | A PRO Studios | |

| 1974 | Heidi, Girl of the Alps | Hayao Miyazaki | Isao Takahata | Nippon Animation |

| 1978 | Future Boy Conan | Isao Takahata

Hayao Miyazaki |

Nippon Animation | |

| 1979 | Anne of the Green Gables | Hayao Miyazaki | Isao Takahata | Nippon Animation |

- Feature Films:

| Date | Film | Design/Animation | Director | Studio/Distributor |

| 1979 | The Castle of Cagliostro | Hayao Miyazaki | Hayao Miyazaki | Tokyo Movie Shinsha/ Toho/ 1st film directed by Miyazaki |

Case Study: 10 feature films

| Nº | Date | Film | Design/Animation | Director | Studio/Distr. |

| 1 | 1984 | Nausicaä in the Valley of the wind | Hayao Miyazaki | Hayao Miyazaki | Topcraft/Toei |

Studio Ghibli Films:

| Nº | Date | Film | Design/Animation | Director | Studio/Distr. |

| 2 | 1985 | Laputa: Castle in the Sky | Hayao Miyazaki | Hayao Miyazaki | 1st Studio Ghibli film |

| 3 | 1988 | My Neighbor Totoro | Hayao Miyazaki | Hayao Miyazaki | Studio Ghibli |

| 4 | 1989 | Kiki’s Delivery Service | Hayao Miyazaki | Hayao Miyazaki | Studio Ghibli |

| 5 | 1992 | Porco Rosso | Hayao Miyazaki | Hayao Miyazaki | Studio Ghibli |

| 6 | 1997 | Princess Mononoke | Hayao Miyazaki | Hayao Miyazaki | Studio Ghibli |

| 7 | 2001 | Spirited Away | Hayao Miyazaki | Hayao Miyazaki | Studio Ghibli |

| 8 | 2004 | Howl’s Moving Castle | Hayao Miyazaki | Hayao Miyazaki | Studio Ghibli |

| 9 | 2008 | Ponyo | Hayao Miyazaki | Hayao Miyazaki | Studio Ghibli |

| 10 | 2013 | The Wind Rises | Hayao Miyazaki | Hayao Miyazaki | Studio Ghibli |

Cátia Peres is an Assistant Professor and PhD Candidate, at IADE, Creative University, in Portugal.

References

Bendazzi, Giannalberto, (2016). Animation: A World History. Florida: CRC Press.

Bukatman, Scott, (2003). Matters of Gravity: Special Effects and Supermen in the 20th Century. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bukatman, Scott, (2012). The Poetics of Slumberland: Animated Spirits and the Animating Spirit. Berkeley: University of California Press

Cavallaro, Dani, (2006). The Animé Art of Hayao Miyazaki. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co.

Clements, J. (2013). Anime: A History. London: Palgrave Macmillan on behalf of the British Film Institute.

Lamarre, Thomas, (2009). The Anime Machine: A Media Theory of Animation. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press

Miyazaki, Hayao, Cary, B., & Schodt, F. L. (2014). Turning Point: 1997-2008. San Francisco: VIZ Media.

Miyazaki, Hayao, (2009). Starting Point: 1979-1996. San Francisco, CA: VIZ Media.

—. (2016) The Art of Castle in the Sky. San Francisco: VIZ Media.

—. (2005) The Art of Howl’s Moving Castle. San Francisco: VIZ Media.

—. (2006) The Art of Kiki’s Delivery Service. San Francisco: VIZ Media.

—. (2005) The Art of My Neighbor Totoro. San Francisco: VIZ Media.

—. (2017) The Art of Nausicaä of the Valley, Watercolour Impressions. San Francisco: VIZ Media.

—. (2009) The Art of Ponyo. San Francisco: VIZ Media.

—. The Art of Porco Rosso (2005) San Francisco: VIZ Media.

—. (2014) The Art of Princess Mononoke. San Francisco: VIZ Media.

—. (2002) The Art of Spirited Away. San Francisco: VIZ Media.

—. (2014) The Art of The Wind Rises. San Francisco: VIZ Media.

Napier, Susan J., (2005). Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Raffaelli, Lucca & Johnston, (1997). “Disney, Warner Bros. and Japanese Animation.” In Jayne Pilling (ed.) A Reader in Animation Studies, Sydney: John Libbey, pp.112-136.

Wells, Paul. (1998) Understanding Animation. London: Routledge.

Filmography (organized by chronological date):

- Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. (1984). Film. Japan: Hayao Miyazaki

- Laputa: Castle in the Sky. (1986). Film. Japan: Hayao Miyazaki

- My Neighbor Totoro. (1988). Film. Japan: Hayao Miyazaki

- Akira (1988). Film. Japan: Katsuhiro Otomo

- Kiki’s Delivery Service. (1989). Film. Japan: Hayao Miyazaki

- Porco Rosso. (1992). Film. Japan: Hayao Miyazaki

- Ghost in the Shell (1995). Film. Japan: Mamoru Oshii

- Princess Mononoke. (1997). Film. Japan: Hayao Miyazaki

- Spirited Away. (2001). Film. Japan: Hayao Miyazaki

- Howl’s Moving Castle. (2004). Film. Japan: Hayao Miyazaki

- (2008). Film. Japan: Hayao Miyazaki

- The Wind Rises. (2013). Film. Japan: Hayao Miyazaki

- The Kingdom of Dreams & Madness. (2013). Film. Japan: Mami Sunada

© Cátia Peres, Eduardo Corte-Real and Marina Estela Graça

Edited by Amy Ratelle