Introduction

Soviet animation director Yefim Gamburg worked across various genres and styles, producing more than thirty films for both children and adults. While his filmography includes satirical shorts, fairytale adaptations, and musicals, he is most well-known for creating animated parodies (Bendazzi 292). Gamburg is the only Soviet animation director who produced three parody films in three decades: Passion of Spies (Shpionskie Strasti, 1967), a parody of spy films; Robbery, … Style (Ograblenie po…, 1978), a parody of crime films; and Dog in Boots (Pyos v Sapogakh, 1987), a parody of the popular Soviet series D’Artagnan and Three Musketeers (D’Artanyan i Tri Mushketyora, 1978, dir. Georgi Yungvald-Khilkevich).

Each of these films alludes either generally to a genre, or specifically to an existing text. However, what distinguishes parody from an allusion or imitation, is the process of recontextualization and eventual transformation of the target text, which in the end creates a new text (Harries 6). Hence, parody is not a genre, but more of a discursive mode of comedy with its own techniques and methods and no specific form or structure (Neale and Krutnik 19). “Parody is, in another formulation, repetition with critical distance, which marks difference rather than similarity” (Hutcheon 6). Parody simultaneously connects to the target text, but distances from it, through comedic transformation (Harries 6).

Parody is often connected with satire, and this connection will be further examined in this paper. Nevertheless, parody and satire are separate depending on the nature of the target text. Parody focuses on artistic objects, it transforms popular images, scenes, characters, and genres, while satire is aimed toward social norms, customs, economic, and political structures (Rose 7, Gehring 5). “Parody’s target text is always another work of art” (Hutcheon 16), while satire refers to situations or events external to the target text (Tucker 5). Satire is not parody, but satire can be a part of a parodic work and vice versa. Overall, parody is a discursive mode that takes on existing artwork and comedically transforms it from a critical distance.

When parodying (an)other text/s is the main goal of a film, that film can be described as a parody. Such is the case with Gamburg’s three aforementioned films. These films as a whole position themselves within the target’s narrative and stylistic features before recontextualizing and transforming those. This is what separates Gamburg’s films from other notable examples of Soviet animation that employ parody as one of the comedic modes, such as Fedor Khitruk’s Film, Film, Film (Film, Film, Film, 1968). First and foremost, Film, Film, Film satirizes the “intricate choreography of institutional and social relationships” (Roth-Ey 30) it takes to get a film approved for production, and then, once the shooting of the fictional film starts, it parodies Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible (Ivan Grozniy, 1944) with its over-the-top production and somber tone. While parodying Ivan the Terrible is not the main goal of Film, Film, Film, it supports Khitruk’s satire of a film production.

Similar things can be said about other Soviet animated films that utilize parody. The Bremen Town Musicians (Bremenskiye Muzykanty, 1969, dir. Inessa Kovalevskaya) includes caricatures of the popular trio The Fool, The Coward, and The Pro, played by Yuri Nikulin, Georgy Vitsin, and Yevgeny Morgunov in Leonid Gaidai’s live-action comedies; and Treasure Island (Ostrov Sokrovishch, 1988, dir. David Cherkasskiy) references the Soviet spy TV series Seventeen Moments of Spring (Semnadtsat’ Mgnovenii Vesny, 1973, dir. Tatyana Lioznova) when introducing its characters. Both films employ parody, but they are not parody films, since parodying another artwork is not their main goal.

Nevertheless, in addition to Gamburg’s work, there were other Soviet animated films that can be described as parodies. Parody films were already produced during the 1920s, including Mysterious Ring or Fatal Mystery (Tainstvennoye Koltso ili Rokovaya Tayna, 1924, dir. Aleksandr Bushkin), a parody of westerns, and Interplanetary Revolution (Mezhplanetnaya revolyutsiya, 1924, dir. Nikolay Hodatayev, Zenon Komissarenko, Yuriy Merkulov), a parody of the Soviet sci-fi classic Aelita (Aelita, 1924, dir. Yakov Protazanov). Other parodies include Vladimir Tarasov’s Cowboys in the City (Kovboi v gorode, 1973) and Anatoliy Reznikov’s Cowboy One, Cowboy Two (Raz kovboy, dva kovboy, 1981), both of which parody westerns, and Pif-paf, oy-oy-oy! (Pif-paf, oy-oy-oy!, 1980), a parody of five theater genres directed by Garry Bardin and Vitaly Peskov. Additionally, Vladimir Popov’s Sherlock Holmes and I (My s Sherlokom Holmsom, 1985) references the famous novel, but mostly parodies its Soviet adaptation The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson (Priklyucheniya Sherloka Kholmsa i doktora Vatsona, 1979-1986, dir. Igor Maslennikov). This is not an exhaustive list, but it shows the presence of parody in Soviet animation.

Clearly, Yefim Gamburg was not the only Soviet director working with parody. However, he was the one who consistently produced parody films, each time targeting different genres and artworks. This consistency, this continuous relationship with parody and ongoing exploration of parodic methods make Gamburg a unique director within Soviet animation. Although his work is rarely discussed and analyzed in Anglophone animation scholarship, it is usually his parodies that scholars focus on. In his detailed history of world animation, Giannalberto Bendazzi dedicates a short paragraph to Gamburg, bringing up his legacy in parody (292). Laura Pontieri mentions Passion of Spies, as well as satirical Old Precepts (Starye Zavety, 1968), emphasizing Gamburg’s humorous style (122). Maya Katz, in her book about Jewish animators in the Soviet Union, provides a short comment on Passion of Spies, noting its “harmless silliness” (190).

These studies offer short comments on Gamburg’s work and emphasize his contribution to Soviet animation. Additionally, each one of them shines the spotlight on Passion of Spies. Undoubtedly, this film is a milestone in Gamburg’s career, since it defined a relationship with parody that would span decades. It is also the longest film he had directed up till that moment, going just over 20 minutes. However, there is more to the film’s significance. Released in 1968, Passion of Spies is one of the films that marks the return of parody to Soviet animated screen following its short-lived boom during the 1920s. Arguably, the success of Passion of Spies showcased the creative possibilities of parody and opened the doors for more parody films to come for other directors and for Gamburg himself. Therefore, it is worthwhile to take a closer look at the film and analyze how exactly Gamburg approaches and utilizes parody, especially within the Soviet context. However, before moving onto the film’s analysis, it is necessary to discuss the changes in Soviet animation that allowed for a film such as Passion of Spies to happen.

The Thaw Changes Soviet Animation

Arguably, one of the earliest surviving examples of animated Soviet parodies is Mysterious Ring or Fatal Mystery, which spoofs American westerns. What survives of the 1924 film presents a chase between two cowboys that increasingly becomes exaggerated. At one moment, a bullet breaks a horse into pieces, but with the help of a walking glue tube that suddenly enters the frame, the horse is restored and rides back into action. Film historian Oleg Kovalov connects the release of this parody with the popularity of American films among Soviet moviegoers of the time, who were very familiar with stylistic and narrative tropes of Westerns, and, thus, could connect the parody to its target text.

Audiences’ familiarity with an object under parodic attack is one of the key elements of successful parody. As Linda Hutcheon remarks, parody flourishes in periods of cultural sophistication, when parodists can count on the competence of their audiences (19). The Soviet audiences’ exposure to American westerns made Mysterious Ring or Fatal Mystery possible. Unfortunately, following Joseph Stalin’s ascension to power, the import of foreign films practically stopped, while the number of domestic films declined (Kenez 55). Moreover, art was reduced to an idealized depiction of communist values with socialist realism becoming a standard style for Soviet artists. With no foreign films to spoof and no alternative to state-mandated art doctrines, parody, with its critical reflexivity, faded away (Turovskaya 42).

Although parody targets art and not cultural and/or social order, it still can be perceived as a threat to the latter (Troitskiy 93). By recontextualizing another text, parody threatens to destabilize the text’s power, as well as the space it exists in (Gray 2). Hence, parody can be understood as an anarchic force that puts into question the legitimacy of other texts (Hutcheon 75). Art that directly comes from the state, and is shaped and controlled by its ideology, cannot be put into question, and, thus, simply cannot be parodied. From the 1930s onwards, parody either went underground, as exemplified by the literary works of Daniil Kharms (Tucker 15), or simply disappeared, as seen in animation.

The death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 and the ascension of Nikita Khrushchev as the Soviet leader ushered the country into a period known as the Thaw. The Thaw lasted until the mid-1960s and was marked by the relaxation of censorship and the lifting of the Iron Curtain (Bulgakowa 436). As Denis Kozlov writes, the Thaw produced critical shifts in policies, ideas, and artistic practices, diversified culture and language, and opened the country to the social, cultural, and intellectual processes of the West (3). Soviet art became an integral part of transnational cultural flows, participating in film festivals, exhibitions, and book fairs (Kozlov and Gilburd 46). New themes and new styles were allowed to be discussed and explored leading to the slow transformation of Soviet arts, including animation (Pontieri 1).

Under Stalin, animation was sternly pedagogical, dogmatic, and child-oriented (Bendazzi 174). Even though animation in the Thaw continued responding to official policies and social imperatives (Mjolsness and Leigh 101), it stopped being dogmatic, and instead performed its tasks with wit and humor, employing caricature and satire to attack issues of Soviet society (Pontieri 2). The use of satire and humor to address serious topics directed Soviet animation toward adult viewers. Animation was no longer seen as strictly for children. This shift was also reflected in the distribution of animation. For example, the Rossiya Theater in Moscow introduced a special hall dedicated to animation with children’s programming during the day, and adults’ programming in the evenings (Katz 50). In the words of Yefim Gamburg, it was no longer possible to separate adult audiences from animation since animated films began to address important societal topics (Gamburg 19-20).

Although the use of satire was permitted, animators were limited in issues that they could attack, since the political apparatus had influence on animation and the topics it covered (Etty 17). Harmful Western influences, alcoholism, negligence, bureaucracy, and the youth counterculture movement known as stilyagi were among the topics Soviet animators were allowed to criticize (Pikkov 26). With satire permitted, the Thaw witnessed the rise of satirical media such as the film and television anthology series Fuse (Fitil’, 1962-2003), which “belonged to the heavily censored mainstream satire aimed at reinforcing the Soviet state system while denouncing some of its flaws” (Vorobyova 156). Each episode of Fuse consisted of filmed footage and occasional animation, providing a space for Soviet artists to produce satirical works.

Such was the case for Yefim Gamburg, whose directorial debut Fatal Mistake (Rokovaya Oshibka) premiered as a part of a Fuse episode in 1964. It is a story about two tigers who escape a zoo, but then get captured after attacking a cleaning lady in a research institute. At the end of this two-and-a-half-minute short, one tiger implies to another that it should have attacked the academics instead since no one would notice their disappearance. The film contrasts an upbeat and hardworking cleaning lady with academics who smoke, debate, play chess, and read newspapers, thus proclaiming whose labor is useful for Soviet society, and who does not contribute much.

In terms of its style, the film follows the conventions of limited animation: simplicity of form and movement, “the essence without the frills” (Stephenson 50). This marks another change in Soviet animation during the Thaw: a move away from emulating Disney’s style and towards limited animation. Limited animation was a modern way of producing films which also reduced the resources required for their production (Pikkov 224). Limited animation was popularized by UPA (United Production of America), a studio founded by former Disney employees, who rejected naturalism and favored a stylized approach to animation and sound effects (Bottini). Maureen Furniss provides a detailed overview of limited animation, highlighting such characteristics as the re-use of drawings, minimal shapeshifting of characters, extensive camera movement to create a sense of motion, and domination of sound as its key characteristics (133-134).

With these characteristics, limited animation found its way to the Soviet Union and soon became the dominant style of Soviet animation, allowing animators to create an abstractive representation of reality that is conveyed through schematic images and angled forms (Pontieri 81). For example, the zoo that the tigers escape from in Fatal Mistake is represented just by a few lines on a monotonous background. The tigers, as well as human characters, are flat marionettes, whose movements lose fluidity, becoming functional and mechanical (Pontieri 81). Yefim Gamburg notably praised the style in his book Secrets of the Drawn World (Tayny Risovannogo Mira, 1966), in which he also drew readers’ attention to renowned examples such as Valentina and Zinaida Brumberg’s Big Troubles (Bol’shie Nepriiatnosti, 1961) and Fyodor Khitruk’s Story of a Crime (Istoriia Odnogo Prestupleniia, 1962).

The 1960s also witnessed a shift in the distribution of power at Soyuzmultfilm. Mikhail Valkov, the managing director of the studio, allowed the studio’s directors to exercise more control over the formation of their film crews (Katz 51). This decision contributed to the rise of “authorial animation,” with directors controlling every stage of the film’s creation, expressing their visions, and emphasizing individual styles, although they still had to undergo stages of control and evaluation to produce a film (Pontieri 82). With the affordances of limited animation and the ability to express individual styles, Soviet animation transformed into a kaleidoscope of unique projects produced by directors and their teams.

Although Yefim Gamburg’s Passion of Spies technically falls outside of the Thaw, it is the product of the changes that happened in Soviet animation during the period. Attention to adult audiences, satirical responsiveness to modern societal issues, limited animation, and emphasis on the individual styles of creators directly impacted the style and narrative of Gamburg’s parody.

Parody in Passion of Spies: Referencing Soviet Society

Passion of Spies is an animated parody of the detective/spy film genre. Here we view genre as a familiar, meaningful system that is based on interactions with the film medium and that consists of fundamental structural components such as plot, characters, setting, and style (Schatz 16). Parody plays upon our familiarity with a genre and transforms its structural components in a variety of ways. In addition, this study employs social analysis, which demonstrates that any film is entwined with social institutions, social codes, social roles for behavior, and overall cultural context (Thomas 3). Passion of Spies is rooted in Soviet culture and includes several references to various aspects of Soviet life. Thus, social analysis will help to understand how Gamburg engages Soviet society while spoofing cinematic conventions.

The film begins with a card where the title’s letters appear randomly and individually accompanied by sounds of gunshots. Such an opening sets the mood for the piece: there will likely be a confrontation that evolves into an action-packed guns-blazing scene. This opening also immediately bridges the parody to its target genre, the connection that is further highlighted by a subtitle announcing that this is a parody of detective films. Detective films with spies as central characters were booming in the Soviet Union during the 1960s (Sukovata 398), and the audience’s exposure to the genre stimulated the production of this parody. The film evokes and makes fun of various genre tropes and clichés, rather than referencing a specific text.

To work, parody needs to establish a strong narrative and stylistic connection to its target before transforming and lampooning it. In terms of its visuals, Passion of Spies looks different from the majority of Soviet animated films released around the same time by being black and white. Such a decision most likely establishes the connection to the target genre and brings to memory classic examples of Soviet detective films that the adult viewers of the parody might have grown up with, such as High Award (Vysokaya nagrada, 1939, dir. Yevgeni Shneider) or Engineer Kochin’s Error (Oshibka inzhenera Kochina, 1939, dir. Aleksandr Matcheret), in both of which foreign spies attempt to steal blueprints of Soviet innovations. Similarly, the plot of Passion of Spies revolves around another Soviet innovation – a magical dental chair that gives a perfect set of teeth to anyone who sits down. The chief of an unnamed foreign intelligence agency sends the spies to steal the chair to help with his toothache, but the Soviet agents interfere and begin their counter-operation.

While conflict-wise the parody recalls past Soviet spy films, it modernizes the narrative by adding an archetype of the femme fatale, who appears in the second part of the film. The femme fatale is common for American noir and detective films, but not for the Soviet ones. During Stalin’s reign, Soviet films rejected Hollywood genre conventions (Cassiday 57). However, following Stalin’s death and the Thaw, the femme fatale entered Soviet culture, first appearing in spy novels. The image of a beautiful, independent, single, and foreign woman became a common metaphor for the threat or hidden danger in general (Sukovata 397). Stunning and dangerous, the femme fatale quickly entered Soviet cinema, as evident, for example, by The Blue Arrow (Golubaya Strela, 1958, dir. Leonid Estrin), in which a foreign woman seduces an airman and receives secret information from him (Graffy 31).

The archetypal femme fatale often works as a nightclub singer, trapping her victims through an erotic spectacle of song and/or dance (Spicer 91). Since parody mimics the object under attack, making it both a target and a part of the new parodic work, Gamburg introduces his femme fatale named Shtampke as a restaurant singer. Extremely sexualized, wearing a short black dress with deep cleavage, heavy make-up, and big jewelry, Shtampke is performing a song at the restaurant Maturity (Zrelost’), which is a riff on the common name of restaurants in the Soviet Union – Youth (Yunost’). A young man named Valdemar enters the restaurant and coincidentally meets this alluring femme fatale. He sits right in front of the stage and gazes at the femme fatale’s provocative performance, which is further embellished by Shtampke’s singing. Considering that the film is mostly wordless, this is one of two times we hear any actual words. In a few shots, we see Valdemar in the left lower corner gazing upwards at Shtampke with his mouth wide open. He is immediately hooked.

Valdemar is portrayed as a member of the Soviet counterculture stilyagi movement that emerged following World War II. They were a small group of mostly men devoted to leisure, Westernness, and stylishness (Edele 38). The post-Stalin Soviet rulers saw the youth as essential for building a communist utopia, while appealing to their consumption wishes and cultural tastes (Tsipursky 78). However, stilyagi were seen as rejecting the idealist view of communism that was supposed to be upheld by the proletariat (Pontieri 89). Although most people considered the enjoyment of foreign culture compatible with Soviet identity, the state thought otherwise: anything that distracted people from the communist mission had no place in the country (Fürst 345). Thus, stilyagi had to be ridiculed. Soviet satire often attacked young stilyagi for their Westernness, social parasitism and lack of valuable contribution to the state, as seen, for example, in Big Troubles (Pontieri 89).

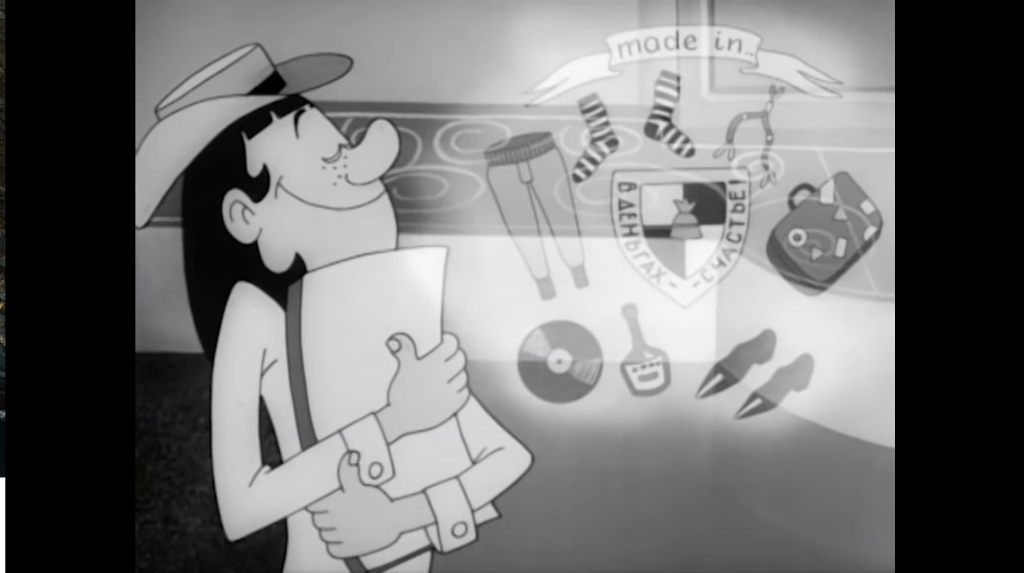

Since Valdemar is a stilyaga, Shtampke manipulates the man into becoming an accomplice by nurturing his fantasies of Western life. Following her performance, she sits down at his table and orders a lavish dinner. She lifts her skirt up, showcases the foreign stocking with the tag “Made in” and offers the magazine titled “Striptease”, with the tag and the magazine’s title written in English. Valdemar enthusiastically accepts the offer and even hugs the magazine (Figure 1). He is seduced, not because of the femme fatale’s sexuality, but because of his obsession with Western consumerist culture. To further highlight how effortless it was to seduce Valdemar, Gamburg uses jump cuts (when the action moves forward but the framing and shot composition remain consistent). When Shtampke sits down with Valdemar, he tries to kiss her, but Gamburg soon cuts to them being further from each other. Then the food appears in a jump cut, and later a pack of cigarettes. Apart from simply showing the longer action in a shorter way, these jump cuts suggest how quickly and smoothly a foreigner can seduce one of stilyagi members. In this seduction scene, Gamburg combines parody and satire, spoofing the archetype of the femme fatale, while poking fun at the stilyagi movement. It is foreign clothes, a magazine, and chic restaurant food that are at the center of seduction.

This scene is a perfect example of what makes Passion of Spies stand out from Soviet animated parody films or films that utilize parody. While others either bring parody to satire (Film, Film, Film), satirize “the West” and capitalists (Interplanetary Revolution), or barely engage with satire at all (Cowboy One, Cowboy Two), Gamburg connects parody with broad satire of Soviet society. Parody of the femme fatale archetype and the seduction scene are intertwined with satire of stilyagi, which, in turn, affects the act of transformation that is key to any parody. As further analysis will show, the stilyagi subculture is just one of several targets of Gamburg’s satire; however, while engaging with satire, he never forgets to continue mimicking and parodically transforming the target genre.

Despite being mocked, Valdemar gets a chance to transform into an exemplary Soviet citizen. He agrees to become an accomplice and place a bomb under the magical dental chair, but the same night he realizes the possible repercussions and eventually confesses to the authorities. He meets a Soviet colonel and hands him the “Striptease” magazine. With over-the-top melodramatic music underscoring the scene, the colonel tosses away the magazine and offers a classic painting, Morning in a Pine Forest (1889) by Ivan Shishkin and Konstantin Savitsky. Valdemar eagerly accepts it, and, when the camera closes on his face, we see a large single tear of joy going down his cheek. This scene mirrors the seduction. In both cases Valdemar is seated at a table: on the left from the femme fatale, and then on the right from the colonel. Each time he is offered something that he enthusiastically accepts, thus joining the side of the one who offers. The seduction is underscored by sultry jazzy music, while the meeting with the colonel has a melodramatic tune. Valdemar is positioned between two sides of the Cold War, who are fighting for the youth, manipulating them with their promises and offers. In the end, Valdemar rejects Westernness and accepts Sovietness. His transformation is highlighted at the film’s end, with his head literally glowing from making the right choice.

Valdemar’s transformation brings him closer to his father, taxi chauffeur and amateur musician Kolichev. Kolichev is an exemplary Soviet citizen, who does important service work, similar to the cleaning lady in Fatal Mistake. He abstains from foreign influences, always keeping at hand his balalaika, a traditional Russian instrument, with which he appears in every single scene. Ironically, it is the art of yesteryear that represents the characters’ Sovietness: balalaika for Kolichev and Morning in a Pine Forest for Valdemar. It prompts a question: if admiration for modern Western culture is problematic, then what does the Soviet Union offer instead? It is interesting how Gamburg uses small stylistic decisions (close-up on a tear, glowing head) and music to mock the possibility of becoming the exemplary communist citizen depicted in government propaganda. Although Gamburg starts by satirizing stilyagi, he ends by exposing the belief that the root of evil is foreign influence and if taken away the youth will become perfect citizens eager to contribute to communist utopia.

The melodramatic underscoring of Valdemar’s transformation highlights an important role music plays in Passion of Spies, also seen with Shtampke’s performance and Kolichev attachment to balalaika. Naturally, Gamburg utilizes music for a parodic purpose. The opening titles have quite a strange theme that combines low piano notes with various cartoonish sounds, such as “bloop-bloop”, “tum-tum” and even quacking. Upon watching the film, this theme feels like an audio representation of its parody. It takes the dark and moody genre (low piano notes) and transforms it via animation (cartoonish sounds); for example, in this film, the bomb, a dangerous device on its own, partially loses its threatening nature since it makes the same quacking noise we hear in the theme. Thus, the opening theme situates the context that will help the viewers readily accept the film as it is (Green 85). The composed score that features cartoonish sounds will be played again during the chase scene, which I will discuss later.

Following Valdemar’s confession, a Soviet agent attempts to arrest the femme fatale, who is disguised as an old lady. In Soviet spy films of the Thaw period, masking was closely associated with foreign spies, resulting from the fear of the hidden other (Graffy 30). Julian Graffy (30) also mentions popular films from the 1950s, in which a spy would be disguised as an elderly local, such as The Case of Lance-Corporal Kochetkov (Sluchay s yefreytorom Kochetkovym, 1955, dir. Alexander Razumny). Thus, in Passion of Spies, the femme fatale’s disguise is related to contemporary genre tropes. By masquerading as an old lady, she is no longer able to rely on her sexuality to defend herself, but she still presents a great danger to the Soviet agent. During their fight, both characters display supernatural strength, lifting park benches, destroying buildings, and throwing punches that cut trees. While fictional spies are usually skillful and prepared for combat, Gamburg takes this trope to an extreme. Additionally, he surprises viewers by reversing traditional gender roles. In the end, the woman knocks down the Soviet agent and hides him in a baby carriage, thus equating him to a helpless baby.

The image of a grown man in a baby carriage is not accidental. The 1960s were a time of preoccupation with men’s vulnerability in Soviet popular culture (Dumančić 12). Marko Dumančić describes how on- and off-screen men were no longer radiating heroism; instead, they were wandering in search of meanings, lacking roots and a clear system of values. Men were seen as in need of protection, a view which culminated in the 1968 article “Protect the Men!” (“Beregite Muzhchin!”) published in the Soviet cultural publication Literaturnaya Gazeta. “The notion that men required supervision resulted in visuals depicting them as infantilized creatures in need of babying” and this kind of image can be seen in Passion of Spies (Dumančić 6). Eventually, it is an actual baby, a witness to the fight, who saves the Soviet agent by contacting the proper authorities.

With the baby’s help, the femme fatale is arrested and brought to an interrogation. Yefim Gamburg subverts the trope of interrogation common for spy films when the film’s femme fatale is confronted by a Soviet general. In a shot that includes both characters, the femme fatale’s face is in the left lower corner with her eyes fearfully looking at the general, who is in the right upper corner of the frame. According to the genre tropes an intense interrogation can be expected. However, the general literally sees into the woman’s mind (Figure 2). He stares at Shtampke, and eventually materializes an illumination onto the woman’s forehead, which shows the pictures of the plan and the location of the secret base. His gaze is so powerful that he even takes out a magnifying glass to see the exact address of the secret base. Since Passion of Spies is a mostly wordless film, this restriction, common to short-form animation at the time, stimulated Gamburg to work around the trope of intense investigation, by presenting an overpowered Soviet general who can easily see into people’s minds. By using familiar scenarios, such as interrogation, Gamburg guides viewers to a certain assumption that is based on existing cultural knowledge. However, he subverts the expectations, keeping interrogation only as a formal element, but transforming it through animation: together with the general, we see into the woman’s mind.

It is also not accidental that it was the femme fatale who revealed the details of the secret operation. In classic noir films, such as Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), the femme fatale always suffers demise and pays for her crimes. In Passion of Spies, she is the only spy who is confronted and captured by the Soviet agents, and it is she who reveals the plan and the hideout, thus marking the end of the spy’s operation. The femme fatale character and her unchanged fate connect Passion of Spies to its target text, the connection that is necessary for a parody to work.

Gamburg also uses other genre conventions to establish a connection with the target text, for example, the chase at the end of the first part. The chase is a common trope for spy films; usually set in an urban environment and utilizing various modes of transportation, the chase is, simply put, a series of credible obstacles to overcome (Long 239). Gamburg begins with a formal genre convention – car hijacking. The spy steals a car driven by Kolichev, threatening him with a gun and even firing it many times. Once again, the connection with the target genre is established, as we also hear dramatic piano notes, which suddenly become embellished by weird cartoon sounds. Similar to the opening theme, Gamburg uses a musical cue indicating that something transformative and parodic is about to take place. Although he continues formal (confrontation on a roof or on top of a moving train) and visual connections to the target genre (top shot, tilted angle, fast-paced editing with short shots), he begins to transform them. The characters move from cars to a train to a plane completely unaffected by any damage to themselves or the vehicles. At some point, Gamburg even pauses the chase, with the Soviet agent casually pulling a wired phone out of his pocket and calling his loved one while sitting on the tail of a plane operated by the spy. While the chase begins following the genre conventions and, thus, being quite realistic, it progressively becomes more and more cartoonish. Hence, Gamburg plays with the audience’s expectations using misdirection, initially presenting specific elements in a manner similar to the target text before transforming them via an unexpected turn (Harries 38).

The chase is not the only time Gamburg plays on the audience’s expectations. At the beginning of the film, a foreign spy lands in Moscow near the Girl with an Oar statue, a famous example of socialist realism done by Ivan Shadr and Romuald Iodko. When the film cuts back to the spy, the camera’s position reveals a Soviet agent inside the statue with his face peeking out. When the spy walks away, the agent opens a hole in the statue’s breasts and takes a photo with an automatic camera. In this scene, Gamburg takes the familiar symbol but completely shifts its characteristics: the female shape is contrasted with the masculine face, and the ornamental statue is revealed to be a spy tool with a hidden camera. Girl with an Oar exists in two worlds: the imagined, where it is a spy device, and the real, where it is public art. Thus, Gamburg references an iconic example of Soviet art, while parodying the various machines, robots, and gadgets that became common in spy films.

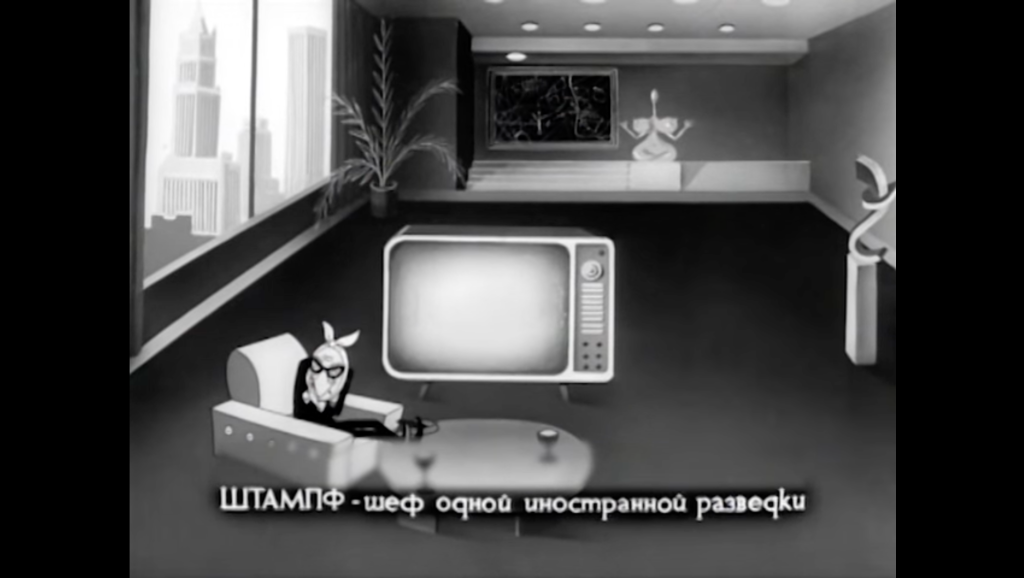

Girl with an Oar is also contrasted with the art located in the office of the foreign agency’s chief. The office houses three art objects: a large abstract painting, a female statue with exaggerated forms, and an abstract statue that looks like a letter S with a ring on it (Figure 3). The connection between modern art and foreign spies recalls Nikita Khrushchev’s angrily public criticism of Soviet modern art during his visit to the “Thirty Years of Moscow Art” exhibition in 1962. Khrushchev’s reaction prompted the campaign for ideological purity with a focus mostly on sculpture and painting (Johnson 9-10). Modernist art became anti-Soviet, and Passion of Spies reflects it: it is evil foreign spies who possess abstract modernist art, while the Soviets enjoy such classics as Morning in a Pine Forest and Girl with an Oar.

Girl with an Oar is not the only place that has a hidden camera. In a later scene, the spy comes close to the magical chair but is ambushed by a Soviet agent. Panicking, the spy runs to the toilet and changes into a footballer uniform. He flushes the old clothes, but, to his detriment, the toilet bank functions as a hidden camera that quickly snaps a photo of the spy. We see the Soviet agents studying that photo in the following scene (Figure 4). The Soviet agents are masters of hidden cameras, placing them in the most unexpected locations. Apart from parodying this common trope of spy films via exaggeration, Gamburg also references Soviet society, specifically mass surveillance practices in the country. Hoffmann states that surveillance was one of the central features of the Soviet system (181). People had to control what they said, thought, and did (Levina 531). While Gamburg does not place himself in opposition to authorities, he exposes the imposed order through parody.

Additionally, Gamburg combines parody with satire of Soviet reality via the characters’ names. Two sides of the conflict share very similar names between themselves: Shtampf, Shtamps, Shtampke, and Shtampi represent the foreign agency, while Sidortsev, Sidorov, Sidorin, and Sidorkin represent the Soviets. We see these names (and a short description of who they are) when introduced to each character (see Figure 3), a stylistic decision that connects the parody to its target text. The similarity in names is further highlighted by the characters’ design: the spies have sharp features and pointed noses, while the Soviets have rounder features and noses. Often in spy films, it is not the real names that are important, but the side that the characters represent, their agencies or states, and Gamburg references this trope. However, such use of the names also illustrates how personal identity and individuality were actively discouraged in the Soviet Union: Sidortsev, Sidorov, Sidorin, and Sidorkin lack distinctive individual characteristics, as they are first and foremost Soviets.

Overall, Yefim Gamburg recreates the tropes of the target genre using their narrative and stylistic conventions. The central conflict, the cast of characters, the story, the key scenes, and various tropes evoke the target’s structure, while black and white visuals, camera angles and positions, editing, and shot compositions resemble the target’s style. However, Gamburg parodically transforms the target genre through misdirection, exaggeration, and broad satire of Soviet reality. As seen in the seduction scene, a satire of stilyagi influences how the target text is parodically transformed. Gamburg does not simply connect parody with satire, but rather specifically references Soviet political and social phenomena, including stilyagi, mass surveillance, and the infantilization of men, without swaying from the structure and style of the target genre. This choice further supports the audience’s engagement with the film: they can recognize references to contemporary spy films, as well as references to their daily lives.

Conclusion

In his first parody, Yefim Gamburg reconceptualizes spy films by spoofing their tropes and conventions, but also by connecting them to Soviet reality. Gamburg brings up existing narrative devices and characters to create a familiar spy setting for the parody, evokes the tropes of spy films before offering viewers unexpected turns, and subverts expectations by misdirection. Gamburg re-affirms tropes of the spy genre while reveling in their “creative destruction” (Balachandran). At the same time, he intertwines parody with satire, attacking the stilyagi movement, commenting on Soviet masculinity, and pointing a finger at the Soviet government. Humorous, satirical, and creative in its reconceptualization, Passion of Spies is an encyclopedia of spy films inexhaustible in gags, puns, and inventive decisions (Asenin 188).

Passion of Spies functions not only as a parody of spy films but as a spy film on its own. Stripped of its gags and humor, the film tells a story, familiar to Soviet viewers, of foreign spies trying to steal innovative Soviet technology. The spies masquerade, recruit an accomplice, and occasionally outsmart Soviet agents, but eventually, they lose. However, this serious spy story is enriched by transformative nonsense, playfulness, and misdirection: the score features cartoonish sounds, the toilet functions as a hidden camera, and the Soviet general has the power to broadcast images from a person’s mind and even examine them closer via a magnifying glass. These are also tied to a satire of Soviet society and its government, referencing mass surveillance and discouragement of individual identity, all of which perfectly fit in a parodic structure, even adding to parodic transformation.

With Passion of Spies Gamburg puts parody firmly onto the Soviet animated screen, showcasing the potential of utilizing this discursive mode and ushering a wave of parody films to which he contributes with two more pictures. He does not reinvent the wheel when it comes to animated parody, but he clearly produces a unique work in the Soviet context. What makes the film special is a combination of different qualities: it is first and foremost parody and it targets a genre instead of a single work; it combines parody with broad satire of Soviet society while employing various references to Soviet culture; it uses satire for parodic transformation of the target genre; it is one of the first parodies after Stalin’s reign, which references tropes from the spy films of that era; it is also one of the longest parodies in Soviet animation that presents a single narrative throughout its runtime; finally, it marks an important step in Gamburg’s directing career and puts him on a path leading to more parody films.

Sergei Glotov, Ph.D. in Media Education from Tampere University, Finland, is interested in audio-visual media literacy, intercultural education, and educational sciences. He published open educational resources about contemporary films and taught film survey and animation history courses. Currently, he works as a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Luxembourg, supporting the development of early childhood education.

Works Cited

Asenin, Sergey. Волшебники Экрана. [Volshebniki Ekrana; Screen Magicians]. Isdatelstvo Iskusstvo, 1974.

Balachandran, Anitha. “Kitne Sholay The? Animated Parodies of a Classic Bollywood Film”. animationstudies 2.0. https://blog.animationstudies.org/?p=1417. Accessed 10 December 2023.

Bendazzi, Giannalberto. Animation: A World History: Volume II: The Birth of Style. Routledge, 2015.

Bottini, Cinzia. Redesigning Animation: United Productions of America. Routledge, 2018.

Bulgakowa, O. (2012). “Cine-Weathers: Soviet Thaw Cinema in the International Context”. The Thaw: Soviet Society and Culture during the 1950s and 1960s, edited by Denis Kozlov, Eleonory Gilburd, University of Toronto Press, 2012, pp. 436-481.

Cassiday, Julie A. “Why Stalinist Cinema Had No Detective Films, or How Three Becomes Two in Engineer Kochin’s Mistake.” Quarterly Review of Film and Video, vol. 31, no.1, 2014, pp. 56-73.

Dentith, Simon. Parody. Routledge, 2000.

Dumančić, Marko. Men Out of Focus: The Soviet Masculinity Crisis in the Long Sixties. University of Toronto Press, 2021.

Edele, Mark. “Strange Young Men in Stalin’s Moscow: The Birth and Life of the Stiliagi, 1945-1953.” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, vol. 50, no. 1, 2002, pp. 37-61.

Etty, John. Graphic Satire in the Soviet Union: Krokodil’s Political Cartoons. University Press of Mississippi, 2018.

Furniss, Maureen. Art in Motion, Revised Edition: Animation Aesthetics. Indiana University Press, 2014.

Fürst, Juliane. Stalin’s Last Generation: Soviet Post-War Youth and The Emergence Of Mature Socialism. Oxford University Press, 2010.

Gamburg, Yefim. Тайны Рисованного Мира. [Tayny Risovannogo Mira; Secrets of The Drawn World]. Soviet Artist, 1966.

Gehring, Wes D. Parody as Film Genre. Greenwood Press, 1999.

Gray, Jonathan. Watching with the Simpsons: Television, Parody, and Intertextuality. Routledge, 2012.

Graffy, Julian. “Scant Sign of Thaw: Fear and Anxiety in the Representation of Foreigners in the Soviet Films of the Khrushchev Years”. Russia and its Other(s) on Film. Studies in Central and Eastern Europe, edited by Stephen Hutchings. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, pp. 27-46.

Green, Jessica. “Understanding the Score: Film Music Communicating to and Influencing the Audience.” The Journal of Aesthetic Education, vol. 40, no. 4, 2010, pp. 81-94.

Harries, Dan. Film Parody. British Film Institute, 2000.

Hoffmann, David L. Cultivating the Masses: Modern State Practices and Soviet Socialism, 1914–1939. Cornell University Press, 2017.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-century Art Forms. University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Johnson, Priscilla. Khrushchev and the Arts: The Politics of Soviet Culture, 1962-1964. The M.I.T. Press, 1965.

Katz, Maya B. Drawing the Iron Curtain: Jews and the Golden Age of Soviet Animation. Rutgers University Press, 2016.

Kenez, Peter. “Soviet Cinema in the Age of Stalin”. Stalinism and Soviet Cinema, Edited by Derek Spring and Richard Taylor, Routledge, 1993, pp. 54-68.

Kovalov, Oleg. Из(л)учение Cтранного. Том 1. [Iz(l)ucheniye Strannogo; The Radiation of the Strange]. Seans, 2016.

Kozlov, Denis. “Introduction”. The Thaw: Soviet Society and Culture during the 1950s and 1960s, edited by Denis Kozlov and Eleonory Gilburd, University of Toronto Press, 2012, pp. 1-17.

Kozlov, Denis and Gilburd, Eleonory. “The Thaw as an Event in Russian History”. The Thaw: Soviet Society and Culture during the 1950s and 1960s, edited by Denis Kozlov, Eleonory Gilburd, University of Toronto Press, 2012, pp. 18-82.

Levina, Marina. “Under Lenin’s Watchful Eye: Growing Up in the Former Soviet Union.” Surveillance & Society, vol. 15, no. 3/4, 2017, pp. 529-534.

Long, Christian B. “Chase Sequences and Transport Infrastructure in Global Hollywood Spy Films”. Global Cinematic Cities: New Landscapes of Film and Media, edited by Johan Andersson and Lawrence Webb, Columbia University Press, 2016, pp. 235-252.

Mjolsness, Lora and Leigh, Michele. She Animates: Gendered Soviet and Russian Animation. Academic Studies Press, 2020.

Neale, Steve and Krutnik, Frank. Popular film and television comedy. Routledge, 2006.

Pikkov, Ülo. “On the Topics and Style of Soviet Animated Films.” Baltic Screen Media Review, vol. 4, 2016, pp. 16-37.

Pontieri, Laura. Soviet Animation and the Thaw of the 1960s. John Libbey Publishing, Ltd, 2012.

Rose, Margaret A. Parody: Ancient, Modern and Post-modern. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Roth-Ey, Kristin. Moscow Prime Time: How the Soviet Union Built the Media Empire that Lost the Cultural Cold War, Cornell University Press, 2014.

Schatz, Thomas. Hollywood Genres: Formulas, Filmmaking, and The Studio System. McGraw-Hill, 1981.

Spicer, Andrew. Film Noir. Routledge, 2002.

Stephenson, Ralph. The Animated Film. The Tantivy Press, 1973.

Sukovata, Viktoria. “Soviet Spy Cinema of the Early Cold War in Context of the Soviet Cultural Politics.” Esboços: histórias em contextos globais, vol. 23, no. 36, 2016, pp. 391-403.

Thomas, Sari, editor. Film/culture: Explorations of Cinema in Its Social Context. Scarecrow Press, 1982.

Thomas, Sari. “Introduction”. Film/culture: Explorations of Cinema in Its Social Context, edited by Sari Thomas. Scarecrow Press, 1982, pp. 1-10.

Troitskiy, Sergey. “Is Parody Dangerous?” The European Journal of Humour Research, vol. 9, no. 2, 2021, pp. 92-111.

Tsipursky, Gleb. Socialist Fun: Youth, Consumption, and State-Sponsored Popular Culture in the Soviet Union, 1945–1970. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016.

Tucker, Janet. “Introduction: Parody, Satire and Intertextuality in Russian Literature”. Against the Grain: Parody, Satire and Intertextuality in Russian Literature, edited by Janet Tucker, Slavica, 2002, pp. 1-18.

Turovskaya, Maya. “The 1930s and 1940s: Cinema in Context”. Stalinism and Soviet Cinema, edited by Derek Spring, Richard Taylor, Routledge, 1993, pp. 34-53.

Vorobyova, Maria. “Soviet Policy in the Sphere of Humour and Comedy.” The European Journal of Humour Research, vol. 9, no. 1, 2021, pp. 155-174.